5. Dominant Strategies

Definition and Concept

A dominant strategy in game theory is a strategy that always results in the best payoff for a player, no matter what the other players do. In simpler terms, it’s the strategy that stands out as the best option for a player in all situations—irrespective of how the other players behave.

To understand this concept, think of a game where you have two choices: one that guarantees the highest payoff for you, no matter what the other player chooses, and another choice that may be better or worse depending on the opponent’s actions. The dominant strategy is the one you choose when you’re guaranteed to come out ahead, regardless of the other player’s decision.

Importance of Dominant Strategies

The concept of dominant strategies is important because it simplifies decision-making for players. In any game, if a player has a dominant strategy, they don’t need to worry about predicting the actions of others in complex ways—they just choose the dominant strategy and expect the best result.

However, while dominant strategies are optimal for the individual player, they can lead to suboptimal outcomes for the group. This creates a situation known as the prisoner’s dilemma, where individual rational choices lead to collective inefficiency.

Example 1: The Prisoner’s Dilemma

One of the most well-known examples of dominant strategies is the Prisoner’s Dilemma. Two suspects are arrested for a crime and placed in separate cells. They are given the choice to either cooperate with each other (stay silent) or defect (betray the other).

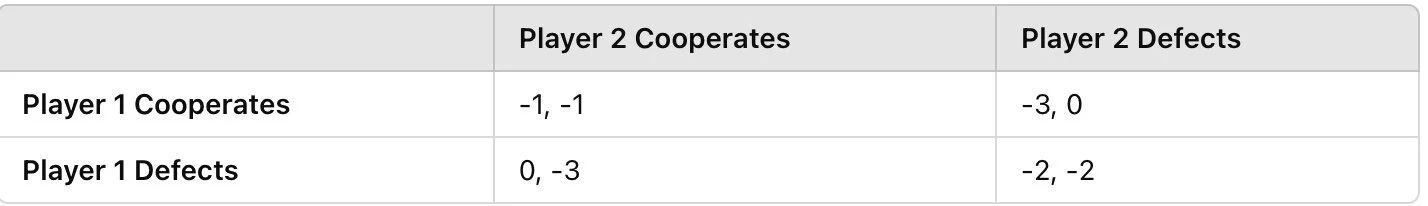

The payoff matrix is as follows:

In this case:

If both players cooperate, they each receive a lighter sentence (-1).

If one defects and the other cooperates, the defector goes free (0), and the cooperator gets a heavy sentence (-3).

If both defect, they both get a moderate sentence (-2).

Here, defection is the dominant strategy because, no matter what Player 2 does, Player 1 is better off defecting. The same applies for Player 2. However, if both players follow their dominant strategy and defect, they both end up worse off than if they had both cooperated.

This demonstrates how dominant strategies can undermine cooperation and result in an outcome that is worse for everyone involved, even though each player is acting in their own best interest.

Example 2: The Battle of Sexes

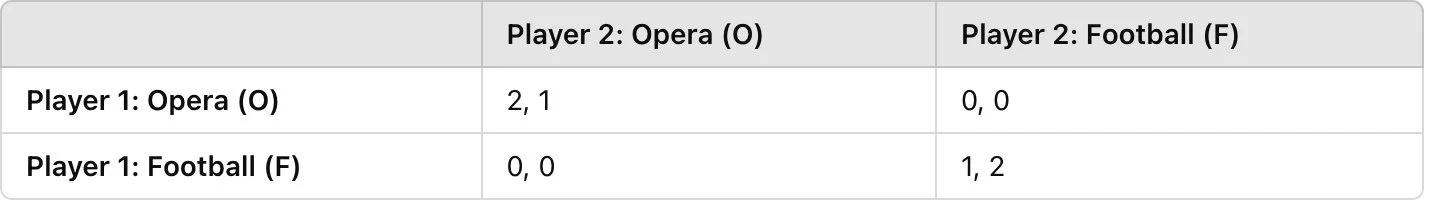

Another classic example is the Battle of the Sexes, where two players—say, a couple—have to decide whether to go to the Opera (O) or to a Football game (F). Both players want to be together, but one prefers the Opera, and the other prefers the Football game. The payoff matrix looks like this:

If both players go to the Opera, they are together, and Player 1 gets a payoff of 2, while Player 2 gets 1 (since they prefer the Opera but are not as enthusiastic).

If both go to the Football game, Player 1 gets a payoff of 1, and Player 2 gets 2 (since they prefer football).

If they go to different places, neither player is happy, resulting in a 0 payoff for both.

Here, there are two Nash Equilibriums:

The first is when both go to the Opera (O, O) — this is stable because neither player wants to change if the other chooses Opera.

The second is when both go to the Football game (F, F) — this is also stable.

In this game, there’s no clear dominant strategy, but each player will prefer to coordinate on one of the two options, and this leads to a coordination problem.

Identifying Dominant Strategies

To identify a dominant strategy in any game, follow these steps:

Construct the Payoff Matrix: List all possible strategies and their corresponding payoffs.

Compare Payoffs: For each player, determine which strategy offers the best outcome given the strategies of the other players.

Check for Dominance: A strategy is dominant if it yields a higher payoff than all other strategies, no matter what the other player chooses.

Real-World Applications of Dominant Strategies

Business and Economics: In highly competitive markets, companies often engage in price competition. The dominant strategy for companies may be to continually lower prices to stay ahead of competitors. While this can result in short-term market share gains, it often leads to lower profit margins and a race to the bottom that harms the industry as a whole.

Environmental Issues: A similar dynamic happens in the overuse of natural resources, where individual nations or corporations act in their own best interest by exploiting resources, even though cooperation would lead to better long-term outcomes for the planet. This situation is reminiscent of the tragedy of the commons.

Advertising: Many companies engage in aggressive advertising spending, believing that outspending their competitors will give them an advantage. This can become a dominant strategy, but it often leads to wasted resources and diminishing returns for all companies in the industry.

Why Dominant Strategies Lead to Suboptimal Outcomes

The primary issue with dominant strategies is that they often ignore the interdependence of players’ decisions. Each player may act in their own self-interest, but this can lead to worse results for everyone involved. When players follow their dominant strategy without cooperation, the group can find itself in a suboptimal equilibrium.

In the Prisoner’s Dilemma, for example, both players end up worse off than if they had cooperated. This outcome reflects the challenge in real-world situations where individual interests can conflict with collective well-being.

Can We Avoid the Dominant Strategy Trap?

In some cases, players can break out of the dominant strategy trap by fostering cooperation. This is often seen in repeated games (such as the Iterated Prisoner’s Dilemma), where players can build trust and cooperation over time. Additionally, external mechanisms such as regulation or binding contracts can encourage players to choose strategies that benefit the group as a whole.

Questions for Reflection – Dominant Strategies

Why is it that players may still choose a dominant strategy even when it leads to worse outcomes for everyone?

Answer: Players choose dominant strategies because they guarantee the best individual outcome. Despite the suboptimal group result, acting in self-interest is often the rational choice from a player's perspective.

In what ways does the concept of dominant strategies conflict with the idea of collective welfare?

Answer: Dominant strategies focus on individual optimization, leading players to overlook the broader impact of their actions on the group. This often results in collective inefficiency, where everyone could do better by cooperating.

How can businesses avoid the negative effects of price wars, where dominant strategies harm the industry?

Answer: Businesses can avoid price wars by cooperating through price stabilization agreements, developing differentiation strategies, or focusing on value-added offerings instead of competing solely on price.

What are some examples of games or scenarios in which players are better off cooperating rather than pursuing their dominant strategy?

Answer: Examples include environmental policies (where cooperation leads to better global outcomes) and trade agreements between countries, where cooperative strategies can ensure mutual benefits in the long run.

How does understanding the role of dominant strategies help in decision-making within competitive environments?

Answer: Understanding dominant strategies allows you to predict others' behaviors and adjust your decisions to optimize your payoff. However, recognizing the risks of collective suboptimal outcomes can help you look for opportunities to cooperate or collaborate instead of just competing.